what did rudolf virchow did to cell theory

| Rudolf Virchow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1821-10-thirteen)xiii Oct 1821 Schivelbein, Pomerania, Kingdom of Prussia, High german Confederation |

| Died | v September 1902(1902-09-05) (anile 80) Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, High german Empire |

| Resting place | Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof, Schöneberg 52°17′Northward 13°xiii′E / 52.28°N 13.22°E / 52.28; thirteen.22 |

| Citizenship | Kingdom of Prussia |

| Didactics | Friedrich Wilhelm University (M.D., 1843) |

| Known for | Cell theory Cellular pathology Biogenesis Virchow's triad |

| Spouse(due south) | Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (a.k.a. Rose Virchow) |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1892) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine Anthropology |

| Institutions | Charité University of Würzburg |

| Thesis | De rheumate praesertim corneae(1843) |

| Doctoral advisor | Johannes Peter Müller |

| Other bookish advisors | Robert Froriep |

| Doctoral students | Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen Walther Kruse |

| Other notable students | Ernst Haeckel Edwin Klebs Franz Boas Adolph Kussmaul Max Westenhöfer William Osler William H. Welch |

| Influenced | Eduard Hitzig Charles Scott Sherrington Paul Farmer |

| Signature | |

| | |

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (;[1] German: [ˈfɪʁço] or [ˈvɪʁço];[2] 13 October 1821 – 5 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and pol. He is known as "the male parent of modern pathology" and as the founder of social medicine, and to his colleagues, the "Pope of medicine".[3] [4] [five]

Virchow studied medicine at the Friedrich Wilhelm University nether Johannes Peter Müller. While working at the Charité hospital, his investigation of the 1847–1848 typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia laid the foundation for public wellness in Frg, and paved his political and social careers. From it, he coined a well known adage: "Medicine is a social science, and politics is null else but medicine on a big scale". His participation in the Revolution of 1848 led to his expulsion from Charité the next yr. He and then published a newspaper Dice Medizinische Reform (The Medical Reform). He took the commencement Chair of Pathological Anatomy at the Academy of Würzburg in 1849. Later on five years, Charité reinstated him to its new Found for Pathology. He co-founded the political political party Deutsche Fortschrittspartei, and was elected to the Prussian House of Representatives and won a seat in the Reichstag. His opposition to Otto von Bismarck's financial policy resulted in duel challenge by the latter. Even so, Virchow supported Bismarck in his anti-Catholic campaigns, which he named Kulturkampf ("culture struggle").[6]

A prolific writer, he produced more than than 2000 scientific writings.[vii] Cellular Pathology (1858), regarded equally the root of modern pathology, introduced the tertiary dictum in cell theory: Omnis cellula e cellula ("All cells come up from cells").[viii] He was a co-founder of Physikalisch-Medizinische Gesellschaft in 1849 and Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pathologie in 1897. He founded journals such equally Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin (with Benno Reinhardt in 1847, later renamed Virchows Archiv), and Zeitschrift für Ethnologie (Journal of Ethnology).[9] The latter is published by German Anthropological Association and the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory, the societies which he also founded.[ten]

Virchow was the commencement to depict and name diseases such as leukemia, chordoma, ochronosis, embolism, and thrombosis. He coined biological terms such as "chromatin", "neuroglia", "agenesis", "parenchyma", "osteoid", "amyloid degeneration", and "spina bifida"; terms such as Virchow's node, Virchow–Robin spaces, Virchow–Seckel syndrome, and Virchow'south triad are named after him. His description of the life cycle of a roundworm Trichinella spiralis influenced the practice of meat inspection. He developed the outset systematic method of dissection,[xi] and introduced hair analysis in forensic investigation.[12] Opposing the germ theory of diseases, he rejected Ignaz Semmelweis'due south idea of disinfecting. He was disquisitional of what he described as "Nordic mysticism" regarding the Aryan race.[13] Every bit an anti-Darwinist, he called Charles Darwin an "ignoramus" and his own student Ernst Haeckel a "fool". He described the original specimen of Neanderthal man as nothing but that of a deformed human.[xiv]

Early on life [edit]

Virchow was born in Schievelbein, in eastern Pomerania, Prussia (now Świdwin, Poland).[15] He was the only child of Carl Christian Siegfried Virchow (1785–1865) and Johanna Maria née Hesse (1785–1857). His begetter was a farmer and the city treasurer. Academically brilliant, he ever topped his classes and was fluent in German, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, English, Arabic, French, Italian and Dutch. He progressed to the gymnasium in Köslin (at present Koszalin in Poland) in 1835 with the goal of condign a pastor. He graduated in 1839 with a thesis titled A Life Total of Piece of work and Toil is not a Burden but a Benediction. However, he chose medicine mainly considering he considered his vox too weak for preaching.[16]

Scientific career [edit]

Memorial stone of Rudolf Virchow in his hometown Świdwin, at present in Poland

In 1839, he received a armed services fellowship, a scholarship for gifted children from poor families to become army surgeons, to study medicine at the Friedrich Wilhelm Academy in Berlin (now Humboldt University of Berlin).[17] He was most influenced past Johannes Peter Müller, his doctoral counselor. Virchow defended his doctoral thesis titled De rheumate praesertim corneae (corneal manifestations of rheumatic disease) on 21 October 1843.[18] Immediately on graduation, he became subordinate medico to Müller.[19] But soon after, he joined the Charité Hospital in Berlin for internship. In 1844, he was appointed as medical assistant to the prosector (pathologist) Robert Froriep, from whom he learned microscopy which interested him in pathology. Froriep was too the editor of an abstruse journal that specialised in foreign piece of work, which inspired Virchow for scientific ideas of France and England.[20]

Virchow published his first scientific paper in 1845, giving the earliest known pathological descriptions of leukemia. He passed the medical licensure exam in 1846 and immediately succeeded Froriep as hospital prosector at the Charité. In 1847, he was appointed to his offset academic position with the rank of privatdozent. Considering his articles did not receive favourable attention from German editors, he founded Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin (at present known as Virchows Archiv) with a colleague Benno Reinhardt in 1847. He edited alone after Reinhardt'southward death in 1852 till his own.[17] This journal published critical articles based on the criterion that no papers would be published that contained outdated, untested, dogmatic or speculative ideas.[16]

Dissimilar his German peers, Virchow had great faith in clinical ascertainment, animal experimentation (to make up one's mind causes of diseases and the furnishings of drugs) and pathological anatomy, specially at the microscopic level, every bit the basic principles of investigation in medical sciences. He went further and stated that the jail cell was the basic unit of measurement of the body that had to be studied to understand illness. Although the term 'jail cell' had been coined in the 1665 by an English scientist Robert Hooke, the edifice blocks of life were nonetheless considered to exist the 21 tissues of Bichat, a concept described by the French md Xavier Bichat.[21] [xx]

The Prussian authorities employed Virchow to study the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia in 1847–1848. It was from this medical campaign that he adult his ideas on social medicine and politics afterward seeing the victims and their poverty. Even though he was non particularly successful in combating the epidemic, his 190-paged Written report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia in 1848 became a turning point in politics and public health in Deutschland.[22] [23] He returned to Berlin on 10 March 1848, and only eight days afterwards, a revolution broke out against the government in which he played an active part. To fight political injustice he helped constitute Die Medizinische Reform (Medical Reform), a weekly newspaper for promoting social medicine, in July of that year. The newspaper ran under the banners "medicine is a social science" and "the physician is the natural attorney of the poor". Political pressures forced him to end the publication in June 1849, and he was expelled from his official position.[24]

In November 1848, he was given an academic engagement and left Berlin for the University of Würzburg to hold Federal republic of germany's first chair of pathological anatomy. During his vi-year flow there, he concentrated on his scientific work, including detailed studies of venous thrombosis and cellular theory. His first major work at that place was a half dozen-volume Handbuch der speciellen Pathologie und Therapie (Handbook on Special Pathology and Therapeutics) published in 1854. In 1856, he returned to Berlin to become the newly created Chair for Pathological Beefcake and Physiology at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Academy, likewise as Director of the newly built Institute for Pathology on the premises of the Charité. He held the latter postal service for the adjacent 20 years.[20] [25] [26]

Cell biology [edit]

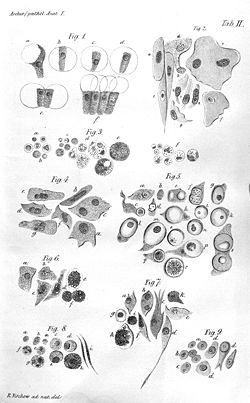

Virchow is credited with several key discoveries. His nigh widely known scientific contribution is his cell theory, which built on the work of Theodor Schwann. He was one of the first to have the work of Robert Remak, who showed that the origin of cells was the division of pre-existing cells.[27] He did not initially accept the testify for cell sectionalisation and believed that it occurs just in sure types of cells. When information technology dawned on him in 1855 that Remak might be right, he published Remak's work as his own, causing a falling-out between the ii.[28]

Virchow was specially influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the primeval and most astute observers of jail cell-life both physiological and pathological". Virchow dedicated his magnum opus Die Cellularpathologie to Goodsir.[29] Virchow's cellular theory was encapsulated in the epigram Omnis cellula east cellula ("all cells (come) from cells"), which he published in 1855.[viii] [20] [30] (The epigram was really coined past François-Vincent Raspail, but popularized past Virchow.)[31] Information technology is a rejection of the concept of spontaneous generation, which held that organisms could arise from nonliving matter. For example, maggots were believed to appear spontaneously in decaying meat; Francesco Redi carried out experiments that disproved this notion and coined the maxim Omne vivum ex ovo ("Every living thing comes from a living affair" — literally "from an egg"); Virchow (and his predecessors) extended this to state that the but source for a living prison cell was some other living cell.[32]

Cancer [edit]

In 1845, Virchow and John Hughes Bennett independently observed aberrant increases in white blood cells in some patients. Virchow correctly identified the condition as a blood disease, and named it leukämie in 1847 (later on anglicised to leukemia).[33] [34] [35] In 1857, he was the kickoff to depict a type of tumour called chordoma that originated from the clivus (at the base of the skull).[36] [37]

Theory of cancer origin [edit]

Virchow was the offset to correctly link the origin of cancers from otherwise normal cells.[38] (His teacher Müller had proposed that cancers originated from cells, but from special cells, which he chosen blastema.) In 1855, he suggested that cancers arise from the activation of dormant cells (perhaps like to cells now known equally stem cells) present in mature tissue.[39] Virchow believed that cancer is caused by astringent irritation in the tissues, and his theory came to be known equally chronic irritation theory. He thought, rather wrongly, that the irritation spread in the course of liquid so that cancer rapidly increases.[40] His theory was largely ignored, as he was proved wrong that it was not by liquid, but past metastasis of the already cancerous cells that cancers spread. (Metastasis was first described past Karl Thiersch in the 1860s.)[41]

He made a crucial ascertainment that certain cancers (carcinoma in the mod sense) were inherently associated with white blood cells (which are now called macrophages) that produced irritation (inflammation). It was but towards the finish of the 20th century that Virchow'due south theory was taken seriously.[42] It was realised that specific cancers (including those of mesothelioma, lung, prostate, float, pancreatic, cervical, esophageal, melanoma, and head and neck) are indeed strongly associated with long-term inflammation.[43] [44] In addition it became clear that prolonged apply of anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin, reduced cancer risk.[45] Experiments also show that drugs that block inflammation simultaneously inhibit tumour germination and development.[46]

The Kaiser's instance [edit]

Virchow was one of the leading physicians to Kaiser Frederick III, who suffered from cancer of the larynx. While other physicians such as Ernst von Bergmann suggested surgical removal of the entire larynx, Virchow was opposed to it because no successful operation of this kind had ever been done. The British surgeon Morell Mackenzie performed a biopsy of the Kaiser in 1887 and sent it to Virchow, who identified it as "pachydermia verrucosa laryngis". Virchow affirmed that the tissues were non malignant, even after several biopsy tests.[47] [48]

The Kaiser died on 15 June 1888. The adjacent 24-hour interval a post-mortem test was performed past Virchow and his assistant. They found that the larynx was extensively damaged by ulceration, and microscopic examination confirmed epidermal carcinoma. Die Krankheit Kaiser Friedrich des Dritten (The Medical Report of Kaiser Frederick III) was published on 11 July under the lead authorship of Bergmann. Only Virchow and Mackenzie were omitted, and they were particularly criticised for all their works.[49] The arguments between them turned into a century-long controversy, resulting in Virchow being defendant of misdiagnosis and malpractice. But reassessment of the diagnostic history revealed that Virchow was right in his findings and decisions. It is now believed that the Kaiser had hybrid verrucous carcinoma, a very rare form of verrucous carcinoma, and that Virchow had no way of correctly identifying it.[47] [48] [50] (The cancer type was correctly identified only in 1948 past Lauren Ackerman.)[51] [52]

Anatomy [edit]

It was discovered approximately simultaneously past Virchow and Charles Emile Troisier that an enlarged left supraclavicular node is i of the primeval signs of gastrointestinal malignancy, commonly of the stomach, or less commonly, lung cancer. This sign has become known as Virchow'southward node and simultaneously Troisier'south sign.[53] [54]

Thromboembolism [edit]

Virchow is also known for elucidating the mechanism of pulmonary thromboembolism (a condition of blood clotting in the blood vessels), coining the terms embolism and thrombosis.[55] He noted that blood clots in the pulmonary artery originate showtime from venous thrombi, stating in 1859:

[T]he detachment of larger or smaller fragments from the end of the softening thrombus which are carried forth by the current of blood and driven into remote vessels. This gives rise to the very frequent process on which I take bestowed the name of Embolia."[56]

Having made these initial discoveries based on autopsies, he proceeded to put forrard a scientific hypothesis; that pulmonary thrombi are transported from the veins of the leg and that the claret has the power to acquit such an object. He then proceeded to prove this hypothesis by well-designed experiments, repeated numerous times to consolidate evidence, and with meticulously detailed methodology. This work rebutted a claim made by the eminent French pathologist Jean Cruveilhier that phlebitis led to clot development and that thus coagulation was the master consequence of venous inflammation. This was a view held by many earlier Virchow's piece of work. Related to this inquiry, Virchow described the factors contributing to venous thrombosis, Virchow'due south triad.[xx] [57]

Pathology [edit]

Virchow founded the medical fields of cellular pathology and comparative pathology (comparison of diseases mutual to humans and animals). His most important work in the field was Cellular Pathology (Dice Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre) published in 1858, every bit a collection of his lectures.[25] This is regarded equally the ground of modern medical science,[58] and the "greatest accelerate which scientific medicine had fabricated since its beginning."[59]

His very innovative work may be viewed as between that of Giovanni Battista Morgagni, whose work Virchow studied, and that of Paul Ehrlich, who studied at the Charité while Virchow was developing microscopic pathology there. One of Virchow'south major contributions to German medical education was to encourage the use of microscopes by medical students, and he was known for constantly urging his students to "call back microscopically". He was the starting time to found a link between infectious diseases between humans and animals, for which he coined the term "zoonoses".[60] He also introduced scientific terms such every bit "chromatin", "agenesis", "parenchyma", "osteoid", "amyloid degeneration", and "spina bifida".[61] His concepts on pathology straight opposed humourism, an ancient medical dogma that diseases were due to imbalanced body fluids, hypothetically called humours, that still pervaded.[62]

Virchow was a great influence on Swedish pathologist Axel Fundamental, who worked as his assistant during Key'due south doctoral studies in Berlin.[63]

Parasitology [edit]

Virchow worked out the life bicycle of a roundworm Trichinella spiralis. Virchow noticed a mass of round white flecks in the muscle of dog and human being cadavers, similar to those described by Richard Owen in 1835. He confirmed by microscopic observation that the white particles were indeed the larvae of roundworms, curled up in the muscle tissue. Rudolph Leukart constitute that these tiny worms could develop into adult roundworms in the intestine of a dog. He correctly asserted that these worms could likewise crusade human helminthiasis. Virchow further demonstrated that if the infected meat is offset heated to 137 °F for x minutes, the worms could not infect dogs or humans.[64] He established that human being roundworm infection occurs via contaminated pork. This directly led to the establishment of meat inspection, which was first adopted in Berlin.[65] [66]

Autopsy [edit]

Virchow was the offset to develop a systematic method of autopsy, based on his knowledge of cellular pathology. The modern autopsy still constitutes his techniques.[67] His outset significant autopsy was on a 50-year-old woman in 1845. He found an unusual number of white claret cells, and gave a detailed clarification in 1847 and named the status as leukämie.[68] One on his autopsies in 1857 was the starting time clarification of vertebral disc rupture.[xviii] [69] His autopsy on a baby in 1856 was the get-go clarification of congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia (the name given by K. Grand. Laurence a century later), a rare and fatal disease of the lung.[70] From his experience of post-mortem examinations of cadavers, he published his method in a minor volume in 1876.[71] His volume was the first to describe the techniques of autopsy specifically to examine abnormalities in organs, and retain important tissues for further examination and demonstration. Unlike any other earlier practitioner, he skilful complete surgery of all trunk parts with torso organs dissected 1 by one. This has become the standard method.[72] [73]

Ochronosis [edit]

Virchow discovered the clinical syndrome which he called ochronosis, a metabolic disorder in which a patient accumulates homogentisic acid in connective tissues and which tin can be identified by discolouration seen under the microscope. He plant the unusual symptom in an autopsy of the corpse of a 67-yr-old man on 8 May 1884. This was the first time this abnormal affliction affecting cartilage and connective tissue was observed and characterised. His description and coining of the name appeared in the Oct 1866 issue of Virchows Archiv.[74] [75] [76]

Forensic work [edit]

Virchow was the commencement to analyse hair in criminal investigation, and made the first forensic report on it in 1861.[77] He was called as an expert witness in a murder case, and he used pilus samples collected from the victim. He became the first to recognise the limitation of pilus as evidence. He constitute that hairs can exist different in an private, that private pilus has feature features, and that hairs from dissimilar individuals can be strikingly like. He concluded that evidence based on pilus assay is inconclusive.[78] His testimony runs:

[T]he hairs plant on the defendant exercise not possess any so pronounced peculiarities or individualities [so] that no one with certainty has the right to assert that they must have originated from the head of the victim.[12]

Anthropology and prehistory biology [edit]

Virchow adult an involvement in anthropology in 1865, when he discovered pile dwellings in northern Germany. In 1869, he co-founded the German Anthropological Association. In 1870 he founded the Berlin Gild for Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory (Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte) which was very influential in coordinating and intensifying German archaeological research. Until his death, Virchow was several times (at to the lowest degree fifteen times) its president, often taking turns with his former pupil Adolf Bastian.[7] As president, Virchow ofttimes contributed to and co-edited the club's main journal Zeitschrift für Ethnologie (Journal of Ethnology), which Adolf Bastian, together with another student of Virchow, Robert Hartman, had founded in 1869.[79] [80]

In 1870, he led a major excavation of the hill forts in Pomerania. He likewise excavated wall mounds in Wöllstein in 1875 with Robert Koch, whose newspaper he edited on the subject.[16] For his contributions in German archaeology, the Rudolf Virchow lecture is held annually in his laurels. He made field trips to Asia Small-scale, the Caucasus, Egypt, Nubia, and other places, sometimes in the company of Heinrich Schliemann. His 1879 journey to the site of Troy is described in Beiträge zur Landeskunde in Troas ("Contributions to the noesis of the mural in Troy", 1879) and Alttrojanische Gräber und Schädel ("Sometime Trojan graves and skulls", 1882).[21] [81]

Anti-Darwinism [edit]

Virchow was an opponent of Darwin's theory of development,[82] [83] and particularly skeptical of the emergent thesis of man evolution.[84] [85] He did not reject evolutionary theory as a whole, and viewed the theory of natural every bit "an immeasurable advance" but that still has no "actual proof."[86] On 22 September 1877, he delivered a public address entitled "The Liberty of Science in the Modern State" before the Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians in Munich. In that location he spoke against the pedagogy of the theory of evolution in schools, arguing that it was as withal an unproven hypothesis that lacked empirical foundations and that, therefore, its teaching would negatively affect scientific studies.[87] [88] Ernst Haeckel, who had been Virchow'south student, later reported that his sometime professor said that "it is quite certain that man did not descend from the apes...non caring in the least that now about all experts of good judgment hold the reverse conviction."[89]

Virchow became one of the leading opponents on the fence over the authenticity of Neanderthal, discovered in 1856, equally distinct species and ancestral to modern humans. He himself examined the original fossil in 1872, and presented his observations before the Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte.[7] He stated that the Neanderthal had not been a primitive form of human, just an abnormal human being being, who, judging past the shape of his skull, had been injured and deformed, and considering the unusual shape of his bones, had been arthritic, rickety, and feeble.[ninety] [91] [92] With such an potency, the fossil was rejected as new species. With this reasoning, Virchow "judged Darwin an ignoramus and Haeckel a fool and was loud and frequent in the publication of these judgments,"[93] and declared that "it is quite sure that man did not descend from the apes."[94] The Neanderthals were afterward accepted as singled-out species of humans, Human neanderthalensis.[95] [96]

On 22 September 1877, at the Fiftieth Conference of the German Association of Naturalists and Physician held in Munich, Haeckel pleaded for introducing evolution in the public schoolhouse curricula, and tried to dissociate Darwinism from social Darwinism.[97] His entrada was because of Herman Müller, a schoolhouse instructor who was banned considering of his teaching a year earlier on the inanimate origin of life from carbon. This resulted in prolonged public debate with Virchow. A few days after Virchow responded that Darwinism was only a hypothesis, and morally dangerous to students. This astringent criticism of Darwinism was immediately taken up past the London Times, from which further debates erupted among English scholars. Haeckel wrote his arguments in the October issue of Nature titled "The Present Position of Evolution Theory", to which Virchow responded in the next issue with an article "The Liberty of Science in the Modern State".[98] Virchow stated that teaching of evolution was "contrary to the conscience of the natural scientists, who reckons only with facts."[86] The debate led Haeckel to write a full book Freedom in Science and Pedagogy in 1879. That yr the issue was discussed in the Prussian House of Representatives and the verdict was in favour of Virchow. In 1882 the Prussian pedagogy policy officially excluded natural history in schools.[99]

Years subsequently, the noted German dr. Carl Ludwig Schleich would recall a conversation he held with Virchow, who was a shut friend of his: "...On to the subject of Darwinism. 'I don't believe in all this,' Virchow told me. 'if I lie on my sofa and accident the possibilities away from me, as another human being may blow the smoke of his cigar, I can, of course, empathise with such dreams. But they don't stand the test of knowledge. Haeckel is a fool. That will be credible one day. As far as that goes, if anything like transmutation did occur it could only happen in the course of pathological degeneration!'"[100]

Virchow's ultimate opinion about evolution was reported a year before he died; in his ain words:

The intermediate form is unimaginable save in a dream... We cannot teach or consent that it is an achievement that homo descended from the ape or other beast.

— Homiletic Review, January, (1901)[101] [102]

Virchow's anti-evolutionism, like that of Albert von Kölliker and Thomas Brownish, did not come from religion, since he was not a believer.[14]

Anti-racism [edit]

Virchow believed that Haeckel's monist propagation of social Darwinism was in its nature politically dangerous and anti-democratic, and he also criticized it because he saw it as related to the emergent nationalist move in Germany, ideas virtually cultural superiority,[103] [104] [105] and militarism.[106] In 1885, he launched a study of craniometry, which gave results contradictory to contemporary scientific racist theories on the "Aryan race", leading him to denounce the "Nordic mysticism" at the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe. Josef Kollmann, a collaborator of Virchow, stated at the aforementioned congress that the people of Europe, exist they High german, Italian, English or French, belonged to a "mixture of various races", further declaring that the "results of craniology" led to a "struggle against any theory concerning the superiority of this or that European race" over others.[107] He analysed the hair, skin, and eye colour of six,758,827 schoolchildren to identify the Jews and Aryans. His findings, published in 1886 and concluding that there could be neither a Jewish nor a German race, were regarded equally a accident to anti-Semitism and the existence of an "Aryan race".[13] [108]

Anti-germ theory of diseases [edit]

Virchow did not believe in the germ theory of diseases, as advocated by Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch. He proposed that diseases came from abnormal activities inside the cells, not from outside pathogens.[60] He believed that epidemics were social in origin, and the way to combat epidemics was political, not medical. He regarded germ theory equally a hindrance to prevention and cure. He considered social factors such every bit poverty major causes of disease.[109] He even attacked Koch's and Ignaz Semmelweis' policy of handwashing as an clarified practice, who said of him: "Explorers of nature recognize no bugbears other than individuals who speculate."[62] He postulated that germs were simply using infected organs as habitats, but were not the cause, and stated, "If I could live my life over once again, I would devote it to proving that germs seek their natural habitat: diseased tissue, rather than being the cause of diseased tissue".[110]

Politics and social medicine [edit]

More a laboratory physician, Virchow was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His credo involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that requires political actions,[111] stating:

Medicine is a social scientific discipline, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine, as a social science, as the science of man beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to try their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must detect the means for their actual solution... Science for its own sake usually ways cypher more science for the sake of the people who happen to be pursuing it. Knowledge which is unable to support action is not genuine – and how unsure is activity without agreement... If medicine is to fulfill her dandy task, then she must enter the political and social life... The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.[112] [113] [114]

Virchow actively worked for social change to fight poverty and diseases. His methods involved pathological observations and statistical analyses. He called this new field of social medicine a "social science". His most important influences could be noted in Latin America, where his disciples introduced his social medicine.[115] For example, his student Max Westenhöfer became Director of Pathology at the medical school of the University of Chile, becoming the most influential advocate. One of Westenhöfer'due south students, Salvador Allende, through social and political activities based on Virchow'south doctrine, became the 29th President of Chile (1970–1973).[116]

Virchow made himself known equally a pronounced pro-democracy progressive in the year of revolutions in Germany (1848). His political views are evident in his Report on the Typhus Outbreak of Upper Silesia, where he states that the outbreak could non be solved by treating private patients with drugs or with minor changes in food, housing, or clothing laws, only only through radical activeness to promote the advancement of an entire population, which could exist achieved simply by "full and unlimited democracy" and "education, freedom and prosperity".[24]

These radical statements and his small-scale part in the revolution caused the government to remove him from his position in 1849, although within a year he was reinstated as prosector "on probation". Prosector was a secondary position in the infirmary. This secondary position in Berlin convinced him to accept the chair of pathological anatomy at the medical schoolhouse in the provincial boondocks of Würzburg, where he continued his scientific research. Six years later, he had attained fame in scientific and medical circles, and was reinstated at Charité Hospital.[twenty]

In 1859, he became a fellow member of the Municipal Council of Berlin and began his career as a civic reformer. Elected to the Prussian Diet in 1862, he became leader of the Radical or Progressive party; and from 1880 to 1893, he was a fellow member of the Reichstag.[21] He worked to improve healthcare conditions for Berlin citizens, especially by working towards modern h2o and sewer systems. Virchow is credited every bit a founder of anthropology[117] and of social medicine, frequently focusing on the fact that affliction is never purely biological, but frequently socially derived or spread.[118]

The duel challenge by Bismarck [edit]

Equally a co-founder and member of the liberal political party Deutsche Fortschrittspartei, he was a leading political adversary of Bismarck. He was opposed to Bismarck'due south excessive military budget, which angered Bismarck sufficiently that he challenged Virchow to a duel in 1865.[21] Virchow declined considering he considered dueling an uncivilized way to solve a conflict.[119] Various English-language sources purport a different version of events, the then-called "Sausage Duel". It has Virchow, being the one challenged and therefore entitled to cull the weapons, selecting 2 pork sausages, i loaded with Trichinella larvae, the other safe; Bismarck declined.[60] [120] [121] Nonetheless, there are no German-language documents confirming this version.

Kulturkampf [edit]

Virchow supported Bismarck in an endeavor to reduce the political and social influence of the Catholic Church, between 1871 and 1887.[122] He remarked that the movement was acquiring "the character of a swell struggle in the interest of humanity". He called it Kulturkampf ("culture struggle")[vi] during the discussion of Paul Ludwig Falk'south May Laws (Maigesetze).[123] Virchow was respected in Masonic circles,[124] and according to one source[125] may have been a freemason, though no official record of this has been plant.

Personal life [edit]

Rudolf and Rose Virchow in 1851

Virchow with his son Ernst and girl Adele

On 24 August 1850 in Berlin, Virchow married Ferdinande Rosalie Mayer (29 Feb 1832 – 21 February 1913), a liberal's daughter. They had three sons and three daughters:[126]

- Karl Virchow (1 Baronial 1851 – 21 September 1912), a chemist

- Hans Virchow (de) (10 September 1852 – vii Apr 1940), an anatomist

- Adele Virchow (one October 1855 – 18 May 1955), the wife of Rudolf Henning, a professor of German studies

- Ernst Virchow (24 Jan 1858 – 5 April 1942)

- Marie Virchow (29 June 1866 – 23 October 1951), the wife of Carl Rabl, an Austrian anatomist

- Hanna Elisabeth Maria Virchow (10 May 1873 – 28 November 1963)

Expiry [edit]

The tomb of Rudolf and Rose Virchow at Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof

Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway. Although he anticipated full recovery, the fractured femur never healed, and restricted his physical activeness. His health gradually deteriorated and he died of heart failure later on eight months, on v September 1902, in Berlin.[16] [127] A state funeral was held on ix September in the Associates Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers. He was buried in the Alter St.-Matthäus-Kirchhof in Schöneberg, Berlin.[128] His tomb was shared by his married woman on 21 February 1913.[129]

Collections and Foundations [edit]

Rudolf Virchow was also a collector. Several museums in Berlin emerged from Virchow'due south collections: the Märkisches Museum, the Museum of Prehistory and Early History, the Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Medical History. In addition, Virchow'southward collection of anatomical specimens from numerous European and not-European populations, which still exists today, deserves special mention. The collection is owned by the Berlin Society for Anthropology and Prehistory. The drove striking the international headlines in 2020 when the two journalists Markus Grill and David Bruser, in cooperation with the archivist Nils Seethaler, succeeded in identifying four skulls of indigenous Canadians that were idea to be lost and which came into Virchow'southward possession through the mediation of the Canadian doctor William Osler in the late 19th century. [130] [131]

Honours and legacy [edit]

- In June 1859, Virchow was elected to Berlin Chamber of Representatives.[26]

- In 1860, he was elected official Member of the Königliche Wissenschaftliche Deputation für das Medizinalwesen (Imperial Scientific Board for Medical Affairs).[25]

- In 1861, he was elected foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

- In 1862, he was elected every bit an international Fellow member of the American Philosophical Gild.[132]

- In March 1862, he was elected to the Prussian House of Representatives.[25]

- In 1873, he was elected to the Prussian Academy of Sciences. He declined to exist ennobled every bit "von Virchow," he was notwithstanding designated Geheimrat ("privy councillor") in 1894.[19]

- In 1880, he was elected member of the Reichstag of the High german Empire.

- In 1881, Rudolf-Virchow-Foundation was established on the occasion of his 60th birthday.[7]

- In 1892, he was appointed Rector of the Berlin Academy.

- In 1892, he was awarded the British Royal Club's Copley Medal.

- The Rudolf Virchow Center, a biomedical inquiry middle in the University of Würzburg was established in January 2002.[133]

- Rudolf Virchow Accolade is given by the Gild for Medical Anthropology for research achievements in medical anthropology.[134]

- Rudolf Virchow lecture, an annual public lecture, is organised by the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz, for eminent scientists in the field of palaeolithic archaeology.

- Rudolf Virchow Medical Gild is based in New York, and offers Rudolf Virchow Medal.[135]

Hospital – Campus Virchow Klinikum, Cardiology Center

- Campus Virchow Klinikum (CVK) is the name of a campus of Charité hospital in Berlin.

- The Rudolf Virchow Monument, a muscular limestone statue, was erected in 1910 at Karlplatz in Berlin.[136]

- Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus was built in 1915 in Berlin, jointly honouring Virchow and Bernhard von Langenbeck. Originally a medical centre, the building is now used as conference centre of the High german Surgical Association (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chirurgie) and the Berlin Medical Association (BMG-Berliner Medizinische Gesellschaft).[137]

- The Rudolf Virchow Study Center is instituted by the European University Viadrina for compiling of the complete works of Virchow.[138]

- Virchow Hill in Antarctica is named after Rudolf Virchow.[139]

Eponymous medical terms [edit]

- Virchow's angle, the angle between the nasobasilar line and the nasosubnasal line

- Virchow's cell, a macrophage in Hansen's disease

- Virchow'due south cell theory, omnis cellula due east cellula – every living cell comes from some other living prison cell

- Virchow's concept of pathology, comparing of diseases common to humans and animals

- Virchow'south affliction, leontiasis ossea, now recognized every bit a symptom rather than a illness

- Virchow'south gland, Virchow'due south node

- Virchow'due south Law, during craniosynostosis, skull growth is restricted to a plane perpendicular to the afflicted, prematurely fused suture and is enhanced in a aeroplane parallel to it.

- Virchow's line, a line from the root of the nose to the lambda

- Virchow'southward metamorphosis, lipomatosis in the heart and salivary glands

- Virchow's method of dissection, a method of autopsy where each organ is taken out one by one

- Virchow's node, the presence of metastatic cancer in a lymph node in the supraclavicular fossa (root of the neck left of the midline), also known every bit Troisier'southward sign

- Virchow's psammoma, psammoma bodies in meningiomas

- Virchow–Robin spaces, enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS) (ofttimes only potential) that surround blood vessels for a short altitude as they enter the brain

- Virchow–Seckel syndrome, a very rare disease also known as "bird-headed dwarfism"

- Virchow skull breaker, a chisel-similar device used to separate the calvaria from the rest of the skull to betrayal the encephalon in autopsies

- Virchow's triad, the classic factors which precipitate venous thrombus formation: endothelial dysfunction or injury, hemodynamic changes, and hypercoagulability

Works [edit]

Virchow was a prolific writer. Some of his works are:[140]

- Mittheilungen über die in Oberschlesien herrschende Typhus-Epidemie (1848)

- Dice Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre., his main work (1859; English translation, 1860): The fourth edition of this work formed the first book of Vorlesungen über Pathologie beneath.

- Handbuch der Speciellen Pathologie und Therapie, prepared in collaboration with others (1854–76)

- Vorlesungen über Pathologie (1862–72)

- Die krankhaften Geschwülste (1863–67)

- Ueber den Hungertyphus (1868)

- Ueber einige Merkmale niederer Menschenrassen am Schädel (1875)

- Beiträge zur physischen Anthropologie der Deutschen (1876)

- Die Freiheit der Wissenschaft im Modernen Staat (1877)

- Gesammelte Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der offentlichen Medizin und der Seuchenlehre (1879)

- Gegen den Antisemitismus (1880)

References [edit]

- ^ "Virchow". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.

- ^ Duden – Virchow

- ^ Silver, G A (1987). "Virchow, the heroic model in medicine: health policy by accolade". American Journal of Public Health. 77 (1): 82–88. doi:x.2105/AJPH.77.1.82. PMC1646803. PMID 3538915.

- ^ Nordenström, Jörgen (2012). The Chase for the Parathyroids. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN978-i-118-34339-five.

- ^ Huisman, Frank; Warner, John Harley (2004). Locating Medical History: The Stories and Their Meanings. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Academy Press. p. 415. ISBN978-0-8018-7861-9.

- ^ a b "Kulturkampf". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 27 Nov 2014.

- ^ a b c d Buikstra, Jane E.; Roberts, Charlotte A. (2012). The Global History of Paleopathology: Pioneers and Prospects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 388–390. ISBN978-0-1953-8980-seven.

- ^ a b Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Britannica Guide to Theories and Ideas That Changed the Mod World. New York, NY: Britannica Educational Pub. in association with Rosen Educational Services. p. 28. ISBN978-one-61530-029-vii.

- ^ Skoczylas, One thousand; Pierzak-Sominka, J; Rudnicki, J (2013). "O formach aktywności dydaktycznej Rudolfa Virchowa w zakresie medycyny". Problems of Applied Sciences. 1: 197–200.

- ^ "Zeitschrift für Ethnologie". Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b Oien, Cary T (2009). "Forensic Pilus Comparison: Background Information for Interpretation". Forensic Science Communications. xi (2): Online.

- ^ a b Silberstein, Laurence J.; Cohn, Robert 50. (1994). The Other in Jewish Thought and History: Constructions of Jewish Civilization and Identity. New York: New York Academy Press. pp. 375–376. ISBN978-0-8147-7990-iii.

- ^ a b Glick, Thomas F. (1988). The Comparative reception of Darwinism. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. pp. 86–87. ISBN978-0-226-29977-8.

- ^ "Virchow, Rudolf". Appletons' Cyclopaedia for 1902. NY: D. Appleton & Company. 1903. pp. 520–521.

- ^ a b c d Weisenberg, Elliot (2009). "Rudolf Virchow, pathologist, anthropologist, and social thinker". Hektoen International Journal. Online. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow". Encyclopedia of Earth Biography. HighBeam™ Research, Inc. 2004. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ a b Weller, Carl Vernon (1921). "Rudolf Virchow—Pathologist". The Scientific Monthly. xiii (i): 33–39. Bibcode:1921SciMo..thirteen...33W. JSTOR 6580.

- ^ a b "Rudolf Ludwig Karl Virchow". Whonamedit? . Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Bagot, Catherine N.; Arya, Roopen (2008). "Virchow and his triad: a question of attribution". British Journal of Haematology. 143 (2): 180–190. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07323.ten. ISSN 1365-2141. PMID 18783400. S2CID 33756942.

- ^ a b c d Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ Taylor, R; Rieger, A (1985). "Medicine as social science: Rudolf Virchow on the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia". International Journal of Health Services. fifteen (4): 547–559. doi:10.2190/xx9v-acd4-kuxd-c0e5. PMID 3908347. S2CID 44723532.

- ^ Azar, HA (1997). "Rudolf Virchow, not simply a pathologist: a re-examination of the report on the typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia". Annals of Diagnostic Pathology. one (one): 65–71. doi:10.1016/S1092-9134(97)80010-10. PMID 9869827.

- ^ a b Brown, Theodore G.; Fee, Elizabeth (2006). "Rudolf Carl Virchow". American Periodical of Public Health. 96 (12): 2104–2105. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.078436. PMC1698150. PMID 17077410.

- ^ a b c d "Virchow's Biography". Berliner Medizinhistorisches Museum der Charité. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ a b Boak, Arthur ER (1921). "Rudolf Virchow—Anthropologist and Archeologist". The Scientific Monthly. xiii (i): 40–45. Bibcode:1921SciMo..13...40B. JSTOR 6581.

- ^ Lois N. Magner A history of the life sciences, Marcel Dekker, 2002, ISBN 0-8247-0824-5, p. 185

- ^ Rutherford, Adam (August 2009). "The Cell: Episode 1 The Hidden Kingdom". BBC4.

- ^ Gardner, D. John Goodsir FRS (1814–1867): Pioneer of cytology and microbiology. J Med. Biog. 2015;25:114–122

- ^ Tixier-Vidal, Andrée (2011). "De la théorie cellulaire à la théorie neuronale". Biologie Aujourd'hui (in French). 204 (4): 253–266. doi:10.1051/jbio/2010015. PMID 21215242.

- ^ Tan SY, Brown J (July 2006). "Rudolph Virchow (1821–1902): "pope of pathology"" (PDF). Singapore Med J. 47 (7): 567–viii. PMID 16810425.

- ^ Virchow, R. (1858). Cellular pathology: As based upon physiological and pathological histology, 20 lectures delivered in the Pathological Constitute of Berlin, during February. Mar. and Apr. 1858. New York: De Witt.

- ^ Degos, L (2001). "John Hughes Bennett, Rudolph Virchow... and Alfred Donné: the first description of leukemia". The Hematology Journal. 2 (1): 1. doi:10.1038/sj/thj/6200090. PMID 11920227.

- ^ Kampen, Kim R. (2012). "The discovery and early understanding of leukemia". Leukemia Inquiry. 36 (ane): half-dozen–13. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2011.09.028. PMID 22033191.

- ^ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (16 November 2010). The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-one-4391-0795-9 . Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ Hirsch, Edwin F (1923). "Sacrococcygeal Chordoma". JAMA. 80 (nineteen): 1369–70. doi:10.1001/jama.1923.02640460019007.

- ^ Lopes, Ademar; Rossi, Benedito Mauro; Silveira, Claudio Regis Sampaio; Alves, Antonio Correa (1996). "Chordoma: retrospective analysis of 24 cases". Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 114 (6): 1312–1316. doi:10.1590/S1516-31801996000600006. PMID 9269106.

- ^ Wagner, RP (1999). "Anecdotal, historical and critical commentaries on genetics. Rudolph Virchow and the genetic ground of somatic environmental". Genetics. 151 (3): 917–920. doi:10.1093/genetics/151.3.917. PMC1460541. PMID 10049910.

- ^ Goldthwaite, Charles A. (20 Nov 2011). "Are Stem Cells Involved in Cancer?". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 22 Dec 2014.

- ^ "The History of Cancer". American Cancer Society, Inc. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Mandal, Aranya (two Dec 2009). "Cancer History". News-Medical.net . Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Balkwill, Fran; Mantovani, Alberto (2001). "Inflammation and cancer: dorsum to Virchow?". The Lancet. 357 (9255): 539–545. doi:x.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. PMID 11229684. S2CID 1730949.

- ^ Coussens, LM; Werb, Z (2002). "Inflammation and cancer". Nature. 420 (6917): 860–867. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..860C. doi:10.1038/nature01322. PMC2803035. PMID 12490959.

- ^ Ostrand-Rosenberg, S.; Sinha, P. (2009). "Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer". The Periodical of Immunology. 182 (8): 4499–4506. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. PMC2810498. PMID 19342621.

- ^ Baron, John A.; Sandler, Robert S. (2000). "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer prevention". Annual Review of Medicine. 51 (1): 511–523. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.511. PMID 10774479.

- ^ Mantovani, Alberto; Allavena, Paola; Sica, Antonio; Balkwill, Frances (2008). "Cancer-related inflammation" (PDF). Nature. 454 (7203): 436–444. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..436M. doi:x.1038/nature07205. hdl:2434/145688. PMID 18650914. S2CID 4429118.

- ^ a b Cardesa, Antonio; Zidar, Nina; Alos, Llucia; Nadal, Alfons; Gale, Nina; Klöppel, Günter (2011). "The Kaiser'due south cancer revisited: was Virchow totally wrong?". Virchows Archiv. 458 (6): 649–657. doi:10.1007/s00428-011-1075-0. PMID 21494762. S2CID 23301771.

- ^ a b Ober, WB (1970). "The instance of the Kaiser's cancer". Pathology Annual. 5: 207–216. PMID 4939999.

- ^ Lucas, Charles T. "Virchow'due south mistake". The Innominate Guild of Louisville. Retrieved 27 Nov 2014.

- ^ Wagener, D.J.Th. (2009). The History of Oncology. Houten: Springer. pp. 104–105. ISBN978-9-0313-6143-4.

- ^ Oliva, H; Aguilera, B (1986). "The harmful biopsies of Kaiser Frederick Iii". Revista Clinica Espanola (in Spanish). 178 (viii): 409–411. PMID 3526428.

- ^ Depprich, Rita A.; Handschel, Jörg G.; Fritzemeier, Claus U.; Engers, Rainer; Kübler, Norbert R. (2006). "Hybrid verrucous carcinoma of the oral crenel: A challenge for the clinician and the pathologist". Oral Oncology Extra. 42 (2): 85–ninety. doi:x.1016/j.ooe.2005.09.006.

- ^ Loh, Keng Yin; Yushak, Abd Wahab (2007). "Virchow'due south Node (Troisier'due south Sign)". New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (3): 282. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm063871. PMID 17634463.

- ^ Sundriyal, D; Kumar, N; Dubey, S. K; Walia, Chiliad (2013). "Virchow's node". BMJ Case Reports. 2013: bcr2013200749. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-200749. PMC3794256. PMID 24031077.

- ^ Kumar, D. R.; Hanlin, Eastward.; Glurich, I.; Mazza, J. J.; Yale, S. H. (2010). "Virchow's contribution to the understanding of thrombosis and cellular biology". Clinical Medicine & Research. 8 (three–4): 168–172. doi:ten.3121/cmr.2009.866. PMC3006583. PMID 20739582.

- ^ Murray, T. Jock (2006). Huth, Edward J. (ed.). Medicine in Quotations: Views of Health and Disease Through the Ages (ii ed.). Philadelphia, US: American College of Physicians. p. 115. ISBN978-1-93051-367-ix.

- ^ Dalen, James E. (2003). Venous Thromboembolism. New York: Marcel Decker, Inc. ISBN978-0-8247-5645-one.

- ^ Reese, DM (1998). "Fundamentals—Rudolf Virchow and modern medicine". The Western Journal of Medicine. 169 (two): 105–108. PMC1305179. PMID 9735691.

- ^ Knatterud, Mary E. (2002). Kickoff Do No Harm: Empathy and the Writing of Medical Journal Articles. New York: Routledge. pp. 43–45. ISBN978-0-4159-3387-two.

- ^ a b c Schultz, Myron (2008). "Rudolf Virchow". Emerg Infect Dis. 14 (9): 1480–1481. doi:10.3201/eid1409.086672. PMC2603088.

- ^ Titford, Thousand. (21 April 2010). "Rudolf Virchow: Cellular Pathologist". Laboratory Medicine. 41 (5): 311–312. doi:10.1309/LM3GYQTY79CPYLBI.

- ^ a b Etzioni, Amos; Ochs, Hans D. (2014). Chief Immunodeficiency Disorders: A Historic and Scientific Perspective. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 3–four. ISBN978-0-12-407179-7.

- ^ Ljunggren, Magnus (7 September 2006). "Utforskare av kroppens okända passager". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ "Discovery of Life Cycle". Trichinella.org. Archived from the original on xix March 2014. Retrieved 24 Nov 2014.

- ^ Nöckler, Grand (2000). "Electric current condition of the discussion on the certification of so-called "Trichinella-free areas"". Berliner und Munchener Tierarztliche Wochenschrift. 113 (four): 134–138. PMID 10816912.

- ^ Saunders, L. Z. (2000). "Virchow'due south Contributions to Veterinarian Medicine: Celebrated Then, Forgotten Now". Veterinary Pathology. 37 (3): 199–207. doi:10.1354/vp.37-3-199. PMID 10810984. S2CID 19501338.

- ^ "Dissection: History of autopsy". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902)". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 25 (2): 91–92. 1975. doi:10.3322/canjclin.25.2.91. PMID 804974. S2CID 1806845.

- ^ Maurice-Williams, R.Due south. (2013). Spinal Degenerative Affliction. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 2. ISBN978-1-4831-9340-iii.

- ^ Hwang, Joon Ho; Kim, Joo Heon; Hwang, Jung Ju; Kim, Kyu Soon; Kim, Seung Yeon (2014). "Pneumonectomy instance in a newborn with congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 29 (4): 609–13. doi:10.3346/jkms.2014.29.four.609. PMC3991809. PMID 24753713.

- ^ Saukko, Pekka J; Pollak, Stefan (2009). "Dissection". Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science. Vol. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:x.1002/9780470061589.fsa036. ISBN978-0-470-01826-two.

- ^ Finkbeiner, Walter E; Ursell, Philip C; Davis, Richard L (2009). Autopsy Pathology: A Manual and Atlas (two ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Wellness Sciences. p. 6. ISBN978-1-4160-5453-5.

- ^ Skowronek, R; Chowaniec, C (2010). "The evolution of autopsy technique--from Virchow to Virtopsy". Archiwum Medycyny Sadowej I Kryminologii. 60 (1): 48–54. PMID 21180108.

- ^ Virchow, RL (1966) [1866]. "Rudolph Virchow on ochronosis.1866". Arthritis and Rheumatism. 9 (1): 66–71. doi:x.1002/art.1780090108. PMID 4952902.

- ^ Benedek, Thomas G. (1966). "Rudolph virchow on ochronosis". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 9 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1002/art.1780090108. PMID 4952902.

- ^ Wilke, Andreas; Steverding, Dietmar (2009). "Ochronosis every bit an unusual cause of valvular defect: a example report". Journal of Medical Instance Reports. 3 (1): 9302. doi:x.1186/1752-1947-iii-9302. PMC2803825. PMID 20062791.

- ^ Committee on Science, Engineering science, and Police, Federal Judicial Eye, National Research Council, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on the Development of the Tertiary Edition of the Reference Transmission on Scientific Testify (2011). Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence (3 ed.). US: National Academies Press. p. 112. ISBN978-0-3092-1425-4. CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Inman, Keith; Rudin, Norah (2000). Principles and Exercise of Criminalistics the Profession of Forensic Science. Hoboken: CRC Press. p. l. ISBN978-1-4200-3693-0.

- ^ "Zeitschrift für Ethnologie: Periodical Info". JSTOR . Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "Forepart Matter". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 2: front encompass. 1870. JSTOR 23025919.

- ^ Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier'south New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- ^ Hodgson, Geoffrey Martin (2006). Economics in the Shadows of Darwin and Marx. Edward Elgar Publishing., p. 14 ISBN 978-1-78100-756-three

- ^ Vucinich, Alexanderm (1988), Darwin in Russian Thought. University of California Press. p. 4 ISBN 978-0-520-06283-2

- ^ Robert Bernasconi (2003). Race and Anthropology: De la pluralité des races humaines. Thoemmes. p. XII

- ^ Ian Tattersall (1995). The Fossil Trail. Oxford paperbacks. Oxford University Press, p. 22 ISBN 978-0-19-510981-viii

- ^ a b Boak, Arthur E. R. (1921). "Rudolf Virchow–Anthropologist and Archeologist". The Scientific Monthly. 13 (1): 40–45. JSTOR 6581.

- ^ Kelly, Alfred (1981). Descent of Darwin: The Popularization of Darwinism in Frg, 1860–1914. UNC Press Books. See: Affiliate four: "Darwinism and the schools". ISBN 978-1-4696-1013-9

- ^ Kuklick, Henrika (2009). New History of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 86–87

- ^ Smithsonian Establishment (1899). Board of Regents Almanac Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution. Board of Regents. p. 472

- ^ Wendt, H. 1960. Tras la huellas de Adán, 3ª edición. Editorial Noguer, Barcelona-México, 566 pp.

- ^ Adam Kupler (1996). The Chosen Primate. Harvard Academy Printing. p. 38 ISBN 978-0-674-12826-ii

- ^ De Paolo, 'Charles (2002); Human Prehistory in Fiction. McFarland. p. 49 ISBN 978-0-7864-8329-7

- ^ American Society of Medical History (1927). Medical Life, Volume 34. Historico-Doctor Press. p. 492

- ^ Walter, Edward; Scott, Mike (2017). "The life and work of Rudolf Virchow 1821-1902: "Cell theory, thrombosis and the sausage duel"". Journal of the Intensive Care Club. eighteen (iii): 234–235. doi:10.1177/1751143716663967. PMC5665122. PMID 29118836.

- ^ White, Suzanna; Gowlett, John A.J.; Grove, Matt (2014). "The identify of the Neanderthals in hominin phylogeny". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 35: 32–l. doi:ten.1016/j.jaa.2014.04.004.

- ^ Rogers, Alan R.; Harris, Nathan S.; Achenbach, Alan A. (2020). "Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors interbred with a distantly related hominin". Science Advances. 6 (8): eaay5483. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay5483. PMC7032934. PMID 32128408.

- ^ Weiss, Sheila Faith (1987). Race Hygiene and National Efficiency: The Eugenics of Wilhelm Schallmayer . Berkeley: Academy of California Press. pp. 67, 179. ISBN978-0-520-05823-i.

- ^ Porter, Theodore M. (2006). Karl Pearson: The Scientific Life in a Statistical Historic period. Princeton: Princeton University Printing. p. 36. ISBN978-i-400-83570-vi.

- ^ Weindling, Paul (1993). Health, Race, and German Politics Between National Unification and Nazism, 1870–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 43. ISBN978-0-521-42397-7.

- ^ Schleich, Carl Ludwig (1936). Those were good days, p. 159. (Notation: this conversation was taken from Schleich's memoirs Besonnte Vergangenheit (1922), and translated into English language by Bernard Miall)

- ^ Ronald L. Numbers (1995). Antievolutionism Before World War I: Volume i of Garland Reference Library of the Humanities. Taylor & Francis. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8153-1802-half-dozen

- ^ Patterson, Alexander (1903). The Other Side of Evolution, Winona Publishing Visitor, p.79

- ^ Hodge, Jonathan; Radick, Gregory (2009). The Cambridge Companion to Darwin (ii ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 238. ISBN978-0-521-71184-five.

- ^ Hawkins, Mike (1998). Social Darwinism in European and American thought, 1860-1945 : Nature as Model and Nature as Threat (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press. p. 138. ISBN978-0-521-57434-1.

- ^ Moore, Randy; Decker, Mark; Cotner, Sehoya (2010). Chronology of the Evolution-creationism Controversy. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO. pp. 121–122. ISBN978-0-313-36287-3.

- ^ Regal, Brian (2004). Human Development : A Guide to Debates. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-Clio. ISBN978-i-85109-418-9.

- ^ Andrea Orsucci, "Ariani, indogermani, stirpi mediterranee: aspetti del dibattito sulle razze europee (1870–1914)" Archived 5 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Cromohs, 1998 (in Italian)

- ^ Zimmerman, Andrew (2008). "Anti-Semitism as Skill: Rudolf Virchow's Schulstatistik and the Racial Composition of Germany". Primal European History. 32 (4): 409–429. doi:x.1017/S0008938900021762. JSTOR 4546903. S2CID 53987293.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow, 1821–1902". The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Retrieved eight July 2014.

- ^ Cayleff, Susan E. (2016). Nature'due south Path: A History of Naturopathic Healing in America. Hopkins Academy Printing. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4214-1903-ix

- ^ Mackenbach, J P (2009). "Politics is nothing just medicine at a larger scale: reflections on public health'southward biggest idea". Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 63 (3): 181–184. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.077032. PMID 19052033. S2CID 24916013.

- ^ Wittern-Sterzel, R (2003). "Politics is nothing else than large calibration medicine"--Rudolf Virchow and his role in the evolution of social medicine". Verhandlungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pathologie. 87: 150–157. PMID 16888907.

- ^ J R A (2006). "Virchow misquoted, role‐quoted, and the real McCoy". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 60 (8): 671. PMC2588080.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow on Pathology Education". The Pathology Guy . Retrieved 28 Nov 2014.

- ^ Porter, Dorothy (2006). "How did social medicine evolve, and where is it heading?". PLOS Medicine. 3 (ten): e399. doi:x.1371/periodical.pmed.0030399. PMC1621092. PMID 17076552.

- ^ Waitzkin, H; Iriart, C; Estrada, A; Lamadrid, S (2001). "Social medicine then and now: lessons from Latin America". American Journal of Public Health. 91 (ten): 1592–601. doi:10.2105/ajph.91.ten.1592. PMC1446835. PMID 11574316.

- ^ Rx for Survival. Global Wellness Champions. Paul Farmer, Dr., PhD | PBS. www.pbs.org

- ^ Virchow, Rudolf Carl (2006). "Study on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia". American Journal of Public Health. 96 (12): 2102–5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.96.12.2102. PMC1698167. PMID 17123938.

- ^ Petra Lennig. "Das verweigerte Duell: Bismarck gegen Virchow" (PDF). www.dhm.de. Deutsches Historisches Museum.

- ^ Isaac Asimov (1991). Treasury of Humor. Mariner Books. p. 202. ISBN978-0-395-57226-ix.

- ^ Cardiff, Robert D; Ward, Jerrold Thousand; Barthold, Stephen W (2008). "'One medicine—one pathology': are veterinary and human pathology prepared?". Laboratory Investigation. 88 (ane): 18–26. doi:ten.1038/labinvest.3700695. PMC7099239. PMID 18040269.

- ^ "This anti-Cosmic crusade was also taken upwardly by the Progressives, especially Rudolf Virchow, though Richter himself was tepid in his occasional support." Authentic High german Liberalism of the 19th century by Ralph Raico

- ^ A leading German school teacher, Rudolf Virchow, characterized Bismarck'southward struggle with the Catholic Church as a Kulturkampf – a fight for culture – past which Virchow meant a fight for liberal, rational principles against the dead weight of medieval traditionalism, obscurantism, and absolutism." from The Triumph of Civilization past Norman D. Livergood and "Kulturkampf \Kul*tur"kampf'\, n. [G., fr. kultur, cultur, culture + kampf fight.] (Ger. Hist.) Lit., civilisation war; – a name, originating with Virchow (1821–1902), given to a struggle between the Roman Cosmic Church building and the German government" Kulturkampf in freedict.co.great britain

- ^ "Rizal'south Berlin assembly, or possibly the give-and-take "patrons" would give their relation ameliorate, were men as esteemed in Masonry as they were eminent in the scientific world—Virchow, for example." in JOSE RIZAL AS A MASON by AUSTIN CRAIG, The Builder Mag, August 1916 – Volume Two – Number 8

- ^ "Information technology was a heady temper for the immature Blood brother, and Masons in Germany, Dr. Rudolf Virchow and Dr. Fedor Jagor, were instrumental in his becoming a member of the Berlin Ethnological and Anthropological Societies." From Dimasalang: The Masonic Life Of Dr. Jose P. Rizal By Reynold S. Fajardo, 33° by Fred Lamar Pearson, Scottish Rite Journal, October 1998

- ^ Marco Steinert Santos (1 September 2008). Virchow: medicina, ciência east sociedade no seu tempo. Imprensa da Univ. de Coimbra. pp. 140–. ISBN978-989-8074-45-4 . Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ^ "Prof. Virchow is Dead. Famous Scientist's Long Illness Ended Yesterday". New York Times. 5 September 1902. Retrieved four August 2012.

- ^ "Prof. Virchow's Funeral. Distinguished Scholars, Scientists, and Doctors in the Throng That Attends the Ceremonies in Berlin". New York Times. nine September 1902. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow tomb". HimeTop . Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Markus Grill/Ralf Wiegand: Die Spur der Schädel Süddeutsche Zeitung, 17.12.xx.

- ^ David Bruser/Markus Grill: The untold story of four Indigenous skulls given abroad by one of Canada's most famous doctors, and the quest to bring them dwelling house. Toronto Star, 17.12.twenty.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow". American Philosophical Society Member History Database . Retrieved eighteen February 2021.

- ^ "The Rudolf Virchow Center". The Rudolf Virchow Center. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 24 Nov 2014.

- ^ "Call for Submissions: Rudolf Virchow Awards". Society for Medical Anthropology. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow Medal". Oregon State University Libraries' Special Collections & Archives Research Center. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow monument". HimeTop . Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Langenbeck-Virchow-Haus" (in German). Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ "Rudolf Virchow Report Center: Rudolf Virchow and Transcultural Wellness Sciences". European University Viadrina. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Virchow Loma. SCAR Blended Antarctic Gazetteer

- ^ Harsch, Ulrich. "Rudolf Virchow". Bibliotecha Augustana (in German). Augsburg University of Applied Sciences. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

Further reading [edit]

- Becher (1891). Rudolf Virchow, Berlin.

- Pagel, J. 50. (1906). Rudolf Virchow, Leipzig.

- Ackerknecht, Erwin H. (1953) Rudolf Virchow: Doctor, Statesman, Anthropologist, Madison.

- Virchow, RLK (1978). Cellular pathology. 1859 special ed., 204–207 John Churchill London, UK.

- The Old Philippines thru Foreign Optics by Tomás de Comyn at Project Gutenberg, available at Project Gutenberg (co-authored by Virchow with Tomás Comyn, Fedor Jagor, and Chas Wilkes)

- Virchow, Rudolf (1870). Menschen- und Affenschadeh Vortrag gehalten am eighteen. Febr. 1869 im Saale des Berliner Handwerkervereins. Berlin: Luderitz,

- Eisenberg L. (1986). "Rudolf Virchow: the physician as politico". Medicine and War. two (4): 243–250. doi:x.1080/07488008608408712. PMID 3540555.

- Rather, 50. J. (1990). A Commentary on the Medical Writings of Rudolf Virchow: Based on Schwalbe's Virchow-Bibliographie, 1843-1901. San Francisco: Norman Publishing. ISBN978-0-9304-0519-9.

External links [edit]

- Works past Rudolf Virchow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or near Rudolf Virchow at Cyberspace Archive

- Works by Rudolf Virchow at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes, bachelor at Projection Gutenberg (co-authored by Virchow with Tomás Comyn, Fedor Jagor, and Chas Wilkes)

- Short biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Students and Publications of Virchow

- A biography of Virchow past the American Association of Neurological Surgeons that deals with his early on work in Cerebrovascular Pathology

- An English translation of the complete 1848 Report on the Typhus Epidemic in Upper Silesia is available in the February 2006 edition of the journal Social Medicine

- Some places and memories related to Rudolf Virchow

- Commodity on Rudolf Virchow in Nautilus retrieved on 28 January 2017.

- Newspaper clippings near Rudolf Virchow in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Virchow

0 Response to "what did rudolf virchow did to cell theory"

Post a Comment